Issue Summary: There are four medical specialties—pathology, emergency medicine, anesthesiology, and radiology (collectively PEAR physicians)—where patients have little or no choice over the physician who treats them. As a result, PEAR physicians can refuse to join insurers’ networks, but cannot be avoided by patients. When PEAR physicians can bill out of network from inside in-network hospitals, patients can be exposed to large, unexpected, and unavoidable medical bills. In addition, the ability to engage in this profitable strategy gives these PEAR physicians the bargaining power to negotiate higher in-network payments than other physicians. These higher in-network payments are passed on to consumers in the form of higher insurance premiums. We show that more than 10% of in-network hospitalizations involve care and a bill from an out-of-network PEAR physician. We estimate this raises private health spending by approximately 8.8%.

Policy Proposal: Policy makers should ban physicians from balance billing patients. They must also determine either the amount or the process through which out-of-network providers get paid. There are two possible approaches. First is baseball-style arbitration where, absent an agreement between a doctor and an insurer, each would submit a bid to an arbitrator who would select between the two options for payment. Second, policy makers could require that hospitals sell a package of care that includes hospital and physician services. This would eliminate the possibility of a patient going to an in-network facility but being treated by an out-of-network provider.

Total Savings: Eliminating out-of-network billing policies that pay PEAR physicians exorbitant rates and instead paying these physicians the same rate as the median orthopedist would lower commercial health spending by approximately 5% (roughly $60 billion) in spending annually.

Introduction

Physicians and hospitals independently negotiate contracts with insurers. As a result, it is possible for a patient to go to an in-network hospital but receive care in that hospital from an out-of-network physician. There are four physician specialties—pathologists, emergency department (ED) physicians, anesthesiologists, and radiologists (collectively, PEAR physicians)—where patients have little or no choice over the physician who treats them. As a result, PEAR physicians can refuse to join insurers’ networks but cannot be avoided by patients.

There are two problems that arise when PEAR physicians bill out of network from inside in-network hospitals. First, patients can receive large and unexpected out-of-network bills from these PEAR physicians, whom they cannot reasonably avoid. Insurers may not cover these bills, which may be hundreds or even thousands of dollars. At present, fewer than half of individuals in the US have the liquidity to pay an unexpected $400 bill (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System 2016). As a result, bills from out-of-network providers can be financially devastating for a large share of the US population.

Second, having the ability to go out of network alters the way physicians negotiate contracts with insurers and gives the physicians outsized bargaining leverage. Most physicians, like orthopedic surgeons and internists, are generally chosen by patients and can be avoided if they are out of network with a patient’s insurer. However, there are several groups of physicians—anesthesiologists, radiologists, pathologists, assistant surgeons, and emergency room physicians—that are not chosen by patients and therefore cannot be avoided. This allows these physicians to negotiate significantly higher in-network payments, which ultimately get passed along to consumers in the form of higher insurance premiums.

The Frequency of Out-of-Network Billing in the US

Based on 2015 data capturing tens of millions of privately insured patients across all 50 states, we observe that 12.3% of patients saw an out-of-network pathologist, 21.9% saw an out-of-network ED physician, 11.8% saw an out-of-network anesthesiologist, and 5.6% saw an out-of-network radiologist (Cooper et al. 2019).

However, out-of-network billing is not evenly distributed across hospitals. Instead, as we illustrate in Exhibit 1, out-of-network billing is concentrated in a small number of hospitals that clearly are allowing out-of-network physicians to deliver care from their facilities as a business strategy. For example, 66.3% of hospitals have fewer than 3% of patients treated by an out-of-network anesthesiologist. However, 2.1% of hospitals in our data have nearly 100% of patients treated by out-of-network physicians. We observe that 6.9% of these hospitals have no in-network ED physicians, 2.2% have no in-network anesthesiologists, and 0.8% have no in-network radiologists.

There are broadly two types of out-of-network bills. The first type results from contracting frictions between insurers and physicians. For example, in the US, there are approximately 45,000 ED physicians, 6,000 hospitals, and 1,000 insurers (American Medical Association 2019 and American Hospital Association 2020). As a result, it is unlikely that every ED physician could have a contract with every insurer that covers all the patients they treat. As an example, an ED physician in a popular vacation destination could see patients from across the country. Even if preferred, it would be a challenge for this ED physician to enter into contracts with insurers from across the country. While an out-of-state patient’s insurer might have a contract with the hospital in the area the patient is visiting, it is possible they might not have a contract with the patient’s ED physician. In these instances, if the physician were not engaging in a deliberate out-of-network strategy, the physician might accept a payment rate that is of the same magnitude as her usual in-network payments.

Exhibit 1: Distribution of Out-of-Network Billing Across Hospitals

A second type of out-of-network billing occurs when physicians deliberately do not participate in insurers’ networks so that they can reap higher payments. As the New York State Department of Financial Services noted, “A relatively small but significant number of out-of-network specialists appear to take advantage of the fact that emergency care must be delivered and [that] advanced disclosure is not typically demanded or even expected by consumers. The fees charged by these providers can, in some instances, be many times larger than what private or public payers typically allow, and are another source of consumer complaints” (New York State Department of Financial Services). In previous work, we have illustrated that physicians compensate hospitals for allowing them to bill out of network from inside these facilities (Cooper et al. 2019). Some physicians engage in profit-sharing schemes with out-of-network providers; others compensate hospitals by altering their clinical practice, such as ordering more imaging studies performed in-hospital or admitting more patients to hospitals (Cooper et al. 2019).

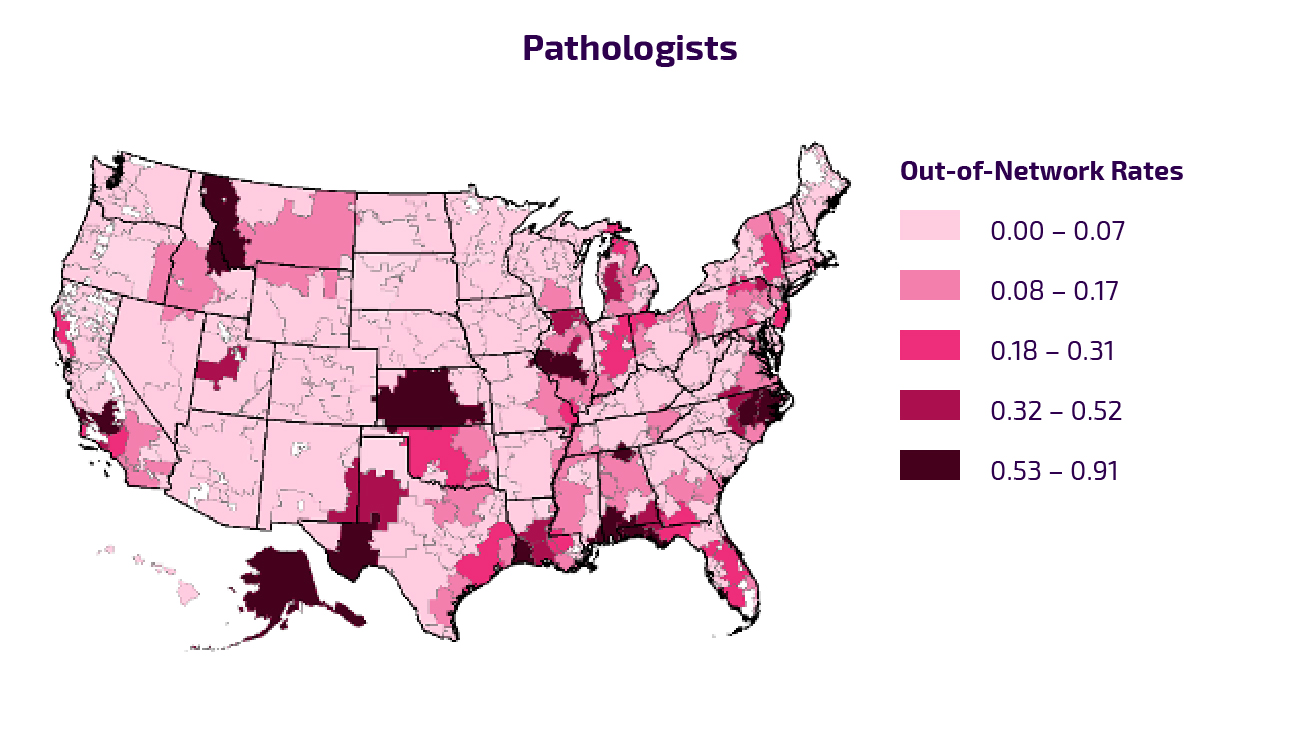

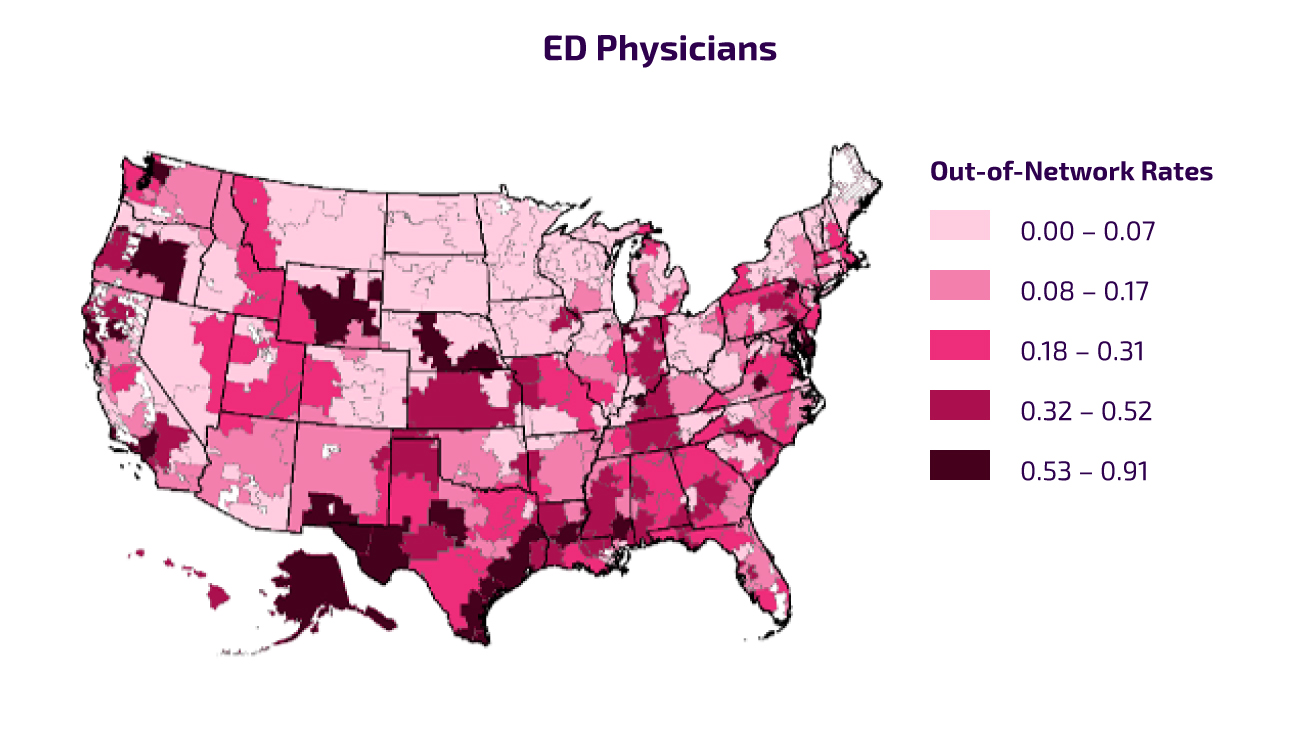

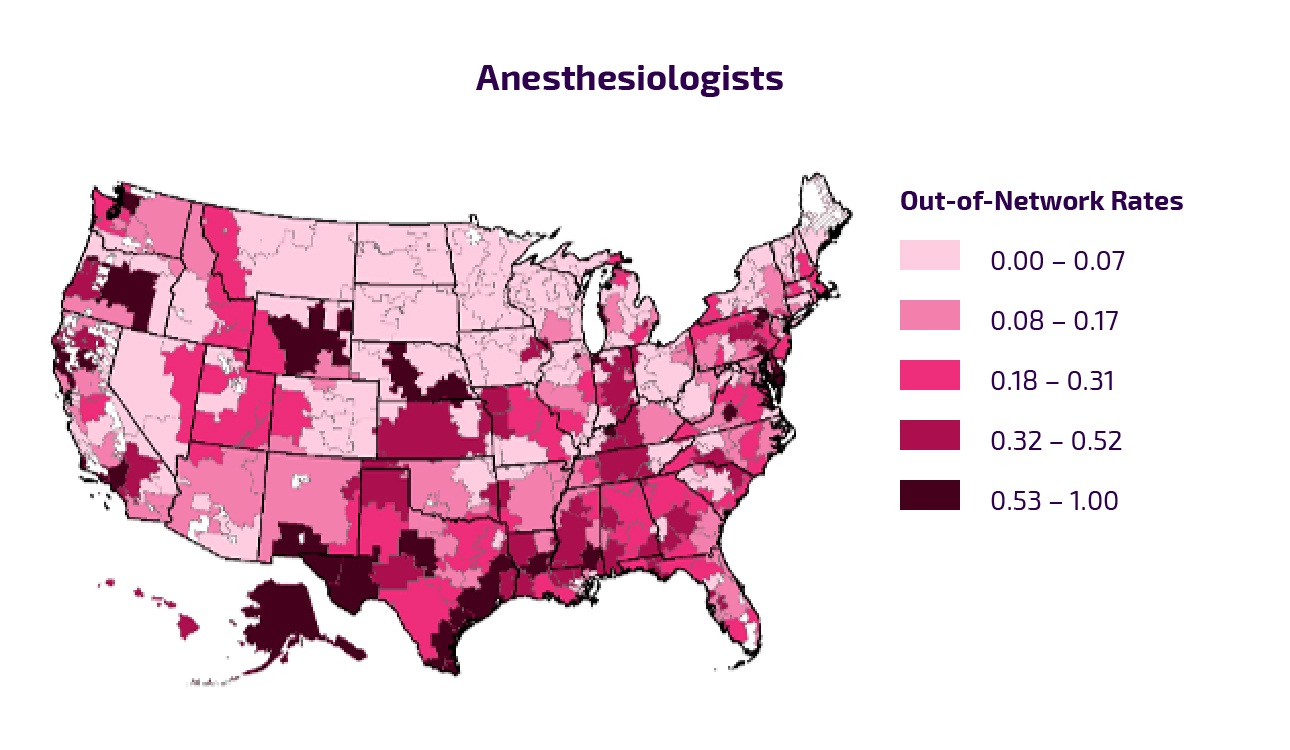

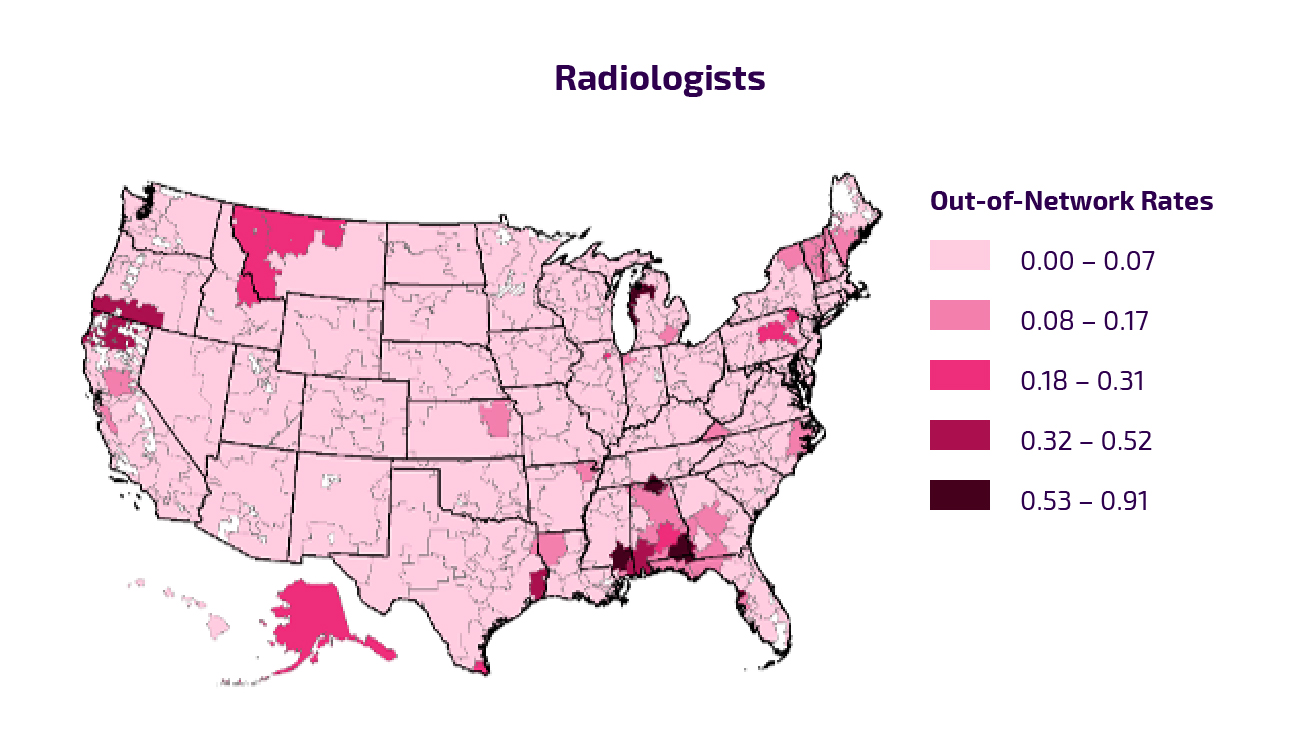

Exhibit 2: Out-of-Network Prevalence by Hospital Referral Regions

In our previous work on out-of-network billing, we have illustrated that out-of-network physicians are more commonly found in for-profit hospitals and in hospitals in more concentrated markets (e.g., those with less competition) (Cooper et al. 2020). Often, physician staffing companies use out-of-network billing as a deliberate strategy to raise revenue.

There is significant variation in the rates at which patients are treated by out-of-network physicians across the US. In general, Texas, New Mexico, and South Carolina have the highest rates of out-of-network billing. Indeed, out-of-network billing tends to occur with higher frequency in states that offer little protection for patients. Exhibit 2 shows the frequency with which patients at in-network hospitals are treated by out-of-network providers, by specialty.

Out-of-Network Billing Charges and Patients’ Potential Cost Exposure

In Exhibit 3, we present the average charges by out-of-network PEAR physicians in dollars and as a percentage of Medicare-regulated payments. The level of charges indicates whether the physician is attempting to extract high payments from the insurer or not. Previous work has found that charges by PEAR physicians tend to be higher than charges by physicians who do not have the ability to execute an out-of-network billing strategy (Bai and Anderson 2017).

In our data, the average charges for these providers are 562% of Medicare rates ($311) for pathologists, 781% of Medicare rates ($974) for ED physicians, 802% of Medicare rates ($2,130) for anesthesiologists, and 452% of Medicare rates ($194) for radiologists. Interestingly, 40.5%, 3.2%, 3%, and 22% of the out-of-network claims for pathologists, ED physicians, anesthesiologists, and radiologists, respectively, have charges below 300% of Medicare payments.

When a patient is treated by an out-of-network doctor, there are four potential outcomes. First, a patient’s insurer could cover the entirety of the charges billed by a patient’s out-of-network provider. These charges are typically significantly higher than in-network payments, so the patient could be exposed to higher cost sharing, and the remaining higher costs of care would be shifted to all consumers in the form of higher premiums.

Second, the patient’s insurer and the out-of-network physician could reach a settlement over an amount lower than the physician’s charges. The patient would pay the cost sharing associated with the rate their insurer and physician negotiate.

Exhibit 3: Out-of-Network Physician Charges and Potential Balance Bills

| Anesthesiologists | Pathologists | Radiologists | ED Physicians | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Out-of-Network Physician Charges | $2,130 (802%) | $311 (562%) | $194 (452%) | $974 (781%) |

| Potential Balance Bills | $1,171 | $177 | $115 | $666 |

Third, the insurer could pay the physician either usual and customary rates or average in-network payments. This could leave the physician to attempt to collect the difference between his or her charges and the median in-network payments (so-called balance billing). In Exhibit 3, we present the average difference between out-of-network physicians’ charges and median in-network payments in our data. This difference is an estimate of the potential balance bills patients could face. As we illustrate in Exhibit 3, these potential balance bills range from $115 to $1,171.

Finally, an insurer could refuse to cover out-of-network physician services. This would leave patients exposed to the entire cost of their care. Physician charges can be substantial. For example, the charges of out-of-network anesthesiologists in the 95th percentile in our data were $6,447.

Ultimately, the outcomes a patient receives when seeing a PEAR physician are a function of the characteristics and policies of the patient’s insurance plan. As a reminder, approximately 50% of Americans do not have the liquidity to pay a $400 unexpected cost without taking on debt (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System 2016). As a result, the cost of receiving care from an out-of-network provider while in the hospital could be financially devastating for a large share of the US population.

Market Characteristics and Estimated Savings

Most physicians face a trade-off when deciding whether or not to join an insurer’s network. On the one hand, joining an insurer’s network gives them access to more patients (volume). However, in order to join an insurer’s network, physicians need to negotiate a price with the insurer that is lower than their usual charges. Crucially, however, PEAR physicians do not need to make the same sort of trade-off as other physicians. Because they are not chosen by patients, PEAR physicians can remain out of network without seeing a substantial decrease in the numbers of patients they treat. Even if they are not paid the entirety of their charges by insurers, these physicians can seek to collect the balance of their bills from patients. Crucially, they are allowed to practice out of network by the hospitals that let them deliver care from inside their facilities.

Because PEAR physicians can remain out of network without losing significant patient volume, these providers have significantly more bargaining leverage with commercial insurers. This is evident from the level of their in-network payments. For example, whereas the average in-network rates for internists for standard offices and orthopedists for knee replacements were 158% and 164% of Medicare rates in 2015, respectively, the in-network rates for pathologists, ED physicians, anesthesiologists, and radiologists as a percentage of Medicare rates in 2015 were 343%, 303%, 367%, and 195%, respectively (Cooper et al. 2019). These higher in-network rates can significantly raise insurance premiums and total health spending.

To give a scale of the impact that out-of-network billing has on total health spending in the US, we estimate the reduction in private health spending that would occur if PEAR physicians were paid at the same level that orthopedic surgeons were paid for knee replacements (i.e., 164% of Medicare rates). Among the privately insured, we estimate that pathologists, ED physicians, anesthesiologists, and radiologists account for 5.9%, 5.7%, 2.9%, and 6.9% of health spending on the privately insured, respectively. We estimate that if they were not allowed to bill out of network and instead negotiated in-network payments on par with orthopedists’ payments, it would lower private health spending by approximately 5%. This would reduce US health expenditures by $60 billion per year.

Policy Options to Eliminate Out-of-Network Billing

Policies to address out-of-network billing by PEAR physicians should have two aims. First, patients should be insulated from balance bills and high cost-sharing payments if they are treated by an out-of-network physician working from an in-network hospital that the patient could not avoid. Second, a policy must restore a competitively set price (or as close to a competitively set price as possible) for out-of-network PEAR physicians. At present, only a handful of states have laws that protect consumers and mechanisms to restore a competitively set rate (New York State Department of Financial Services 2012). Unfortunately, even when states pass meaningful reforms, state laws only apply to individuals enrolled in fully insured insurance plans. State laws addressing out-of-network billing do not apply to the 60% of individuals with private insurance who receive their coverage from plans that self-insure (Claxton et al. 2017).

There are two economically grounded policy approaches for addressing out-of-network bills. The first is introducing a baseball-style arbitration process where physicians and insurers can settle disputes over payments. New York State, for example, introduced an arbitration process together with patient protections in a law passed in 2015. In New York State, if a patient in a fully insured private insurance plan is treated by an out-of-network ED physician, the patient is only exposed to cost sharing equal to what they would have to pay should their provider have been in network. Under the New York law, if the out-of-network provider and the patient’s insurer cannot reach an agreement over a payment, they can initiate a baseball-style arbitration process. Under the law, an arbitrator can determine what the physician will be paid by choosing from either the physician’s original charge or the insurer’s proposed payment.

In a 2017 study, we examined the impact of the New York State law on out-of-network billing in the state. We found that the policy reduced out-of-network billing by 6.8% and actually lowered in-network ED physician payments by 9% (Cooper et al. 2020). Unfortunately, because states cannot regulate ERISA plans, these types of state-based laws do not apply to individuals who receive insurance coverage through employers that self-insure.

A second approach to addressing out-of-network billing is to regulate the nature of the contract between providers and insurers. At present, physicians and hospitals independently negotiate contracts with insurers. Out-of-network billing could also be addressed by requiring hospitals to negotiate payments for PEAR physicians and fold their care into hospital bills. Then it would be up to hospitals to recruit or contract with these PEAR physicians to provide care within their facilities. This type of policy would both eliminate unexpected patient costs and restore competitively set PEAR physician prices.

References

American Hospital Association. 2020. “Fast Facts on US Hospitals.” American Hospital Association. Accessed Nov 17, 2020. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2020/01/2020-aha-hospital-fast-facts-new-Jan-2020.pdf.

American Medical Association. 2019. “AMA Masterfile.” American Medical Association.

Bai, Ge, and Gerard F. Anderson. 2017. “Variation in the Ratio of Physician Charges to Medicare Payments by Specialty and Region.” JAMA 317 (3): 315–318.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 2016. “Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2015.”Washington, DC: Federal Reserve Board. Accessed Feb 2018. https://www.federalreserve.gov/2015-report-economic-well-being-us-households-201605.pdf.

Claxton, Gary, Matthew Rae, Michelle Long, Anthony Damico, Gregory Foster, and Heidy Whitmore. 2017. “Employer Health Benefits: 2017 Annual Survey.” Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research and Educational Trust.

Cooper, Zack and Fiona Scott Morton. 2016. “Out-of-Network Emergency Physician Bills—An Unwelcome Surprise.” New England Journal of Medicine, 375 (20): 1915–1918.

Cooper, Zack, Fiona Scott Morton, and Nathan Shekita. 2020. “Surprise! Out-of-Network Billing for Emergency Care in the United States.” Journal of Political Economy, 128 (9): 3626–3677.

Cooper, Zack, Hao Nguyen, Nathan Shekita, and Fiona Scott Morton. 2019. “Out-of-Network Billing and Negotiated Payments for Hospital-Based Physicians.” Health Affairs, 39 (1): 24–23.

Insurance Information Institute. 2020. “Facts + Statistics: Industry Overview.” Insurance Information Institute. Accessed Nov 17, 2020. https://www.iii.org/fact-statistic/facts-statistics-industry-overview#:~:text=The%20U.S.%20insurance%20industry%20employed,and%20reinsurers%20(28%2C500%20workers).

Klasnja, Predrag and Eric Hekler. 2017. “Variation in the Ratio of Physician Charges to Medicare Payments by Specialty and Region.” JAMA, 317(3): 315–317.

New York State Department of Financial Services. 2012. “An Unwelcome Surprise: How New Yorkers Are Getting Stuck with Unexpected Medical Bills from Out-of-Network Providers.” Albany, NY: New York Department of Financial Services.